10 Product Design Icons from the 20th Century

Following the product design timeline during the 20th century, we can observe that design has evolved to focus on the function rather than the form which dominated 19th-century design movements. Design schools such as post-modernism and Bauhaus contributed to focus on the function of the design and how it serves people’s needs.

The product design timeline indicated a number of iconic designs that were remarked as game-changers and contributed to evolving the industry by introducing new technologies or fulfilling people’s needs achieving the so called human-centered design.

The examples below highlight some of the most successful product design icons through the 20th century and build an understanding of how design can become an icon by focusing on people’s needs and building value through it.

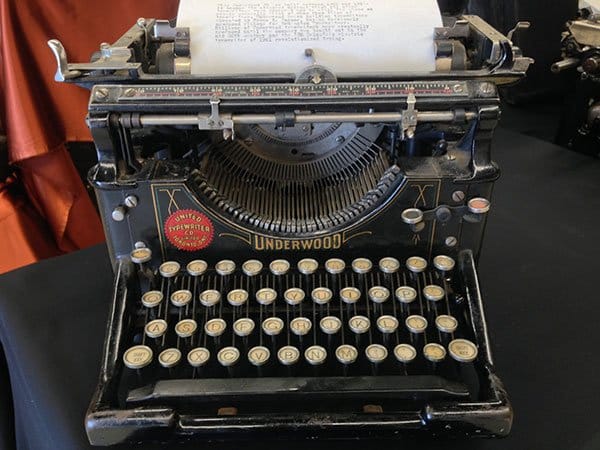

Underwood No. 5 Typewriter (1900)

by Frank X. Wagner

The Underwood No.5 typewriter is one of the most successful typewriter designs in history and dominated the market in the early 20th century, a trend that continued until IBM introduced its Selectric typewriter in 1961. The 84-character model was designed by the German-American inventor Frank X. Wagner and named after the company’s early owner, John T. Underwood. The model was the most successful compared to its related versions, No. 1, 2, 3, and 4.

The Underwood No. 5 was praised for its feature and the adoption of easy-to-use technologies including:

- The type-bar that allowed the typist to print from single type element

- Front stroke mechanism that allows the typist to see what is typed without the necessity to raise the carriage

- The QWERTY universal keyboard, a four-bank keyboard with single shift, and ribbon inking.

The typewriter was used by journalists, writers, and office workers and achieved millions of sales until 1932.

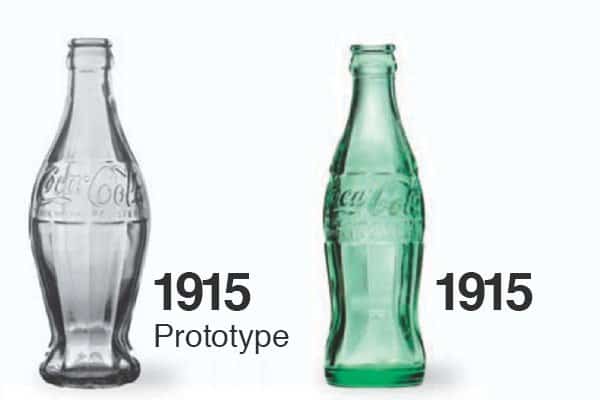

Coca-Cola Bottle (1915)

by Earl R. Dean

The design of the famous Coca-Cola bottle with the contour fluted lines is credited to Earl R. Dean, who was part of the Terra Haute company that was assigned by Coca-Cola to renew the bottle design. The design was inspired by the coca leaf and the kola nut. The father of product design, Raymond Loewy, described it as the “perfect liquid wrapper.” In 1955, Loewy was assigned to design the family-size package while maintaining the same proportion of the previous old design.

Red-Blue Armchair (1918-1923)

by Gerrit Rietveld

The Red-Blue chair reflected the architecture style of Gerrit Rietveld through its horizontal and vertical lines. The armchair was designed in 1918, but later, Bart van der Leck suggested adding colors to it in the early 1920s. The Museum of the Modern Art stated that the yellow, red, and blue were added in 1923.

The Red-Blue armchair was designed to reflect the comfort of the spirit in addition to physical comfort. Reitveld and his colleagues in the De Stijl art movement tended to use the armchair design to reflect the renewed Europe after the World War I.

Bialetti Moka Express (1933)

by Alfonso Bialetti

The most famous coffee maker, designed and developed in Italy by Alfonso Bialetti in 1933 and the only industrial object recognized by the Museum of Modern Art, has remained unchanged since its first model. The coffee maker contains three parts: the lower part contains the boiled water, the middle part contains the coffee (filter section). Once the water is boiled, the pressure pushes the water to the filter area, where it is brewed and poured into the third top part.

Between the period of 1933 to 1939, Bialetti created more than 70,000 example for the product, and development ceased due to Word War II and then continued later with the help of his son Renato. In 1993, the company was acquired by Dondini Group, which retained the product name. Based on the Bialetti website, more than 200 million coffee makers were manufactured.

Volkswagen Beetle (1938)

by Ferdinand Porsche

The car inspired by Nazi leader Adolf Hitler became the most popular car in the world with the highest sales all time. Hitler wanted a cheap and simple car for mass production to be suitable for his new road network. In 1933, he assigned the project to Ferdinand Porsche, who took until 1938 to finish the design. the Volkswagen Beetle is considered the most manufactured car of all time, with 21,529,464 units produced.

The design of the Volkswagen Beetle was based on a rear-engine design, a choice based on Hitler’s requirement that the cost of the car not exceed £86. Later, in 1935, an Austrian engineer developed the engine that reduced the car’s cost, and this engine was used in the car for sixty years. The first prototype, called “Wanderer,” was never sent to production and was only used for Ferdinand’s own transportation. Later, Hitler suggested the shape of the car: “It should look like a Beetle. You have

to look to nature to find out what streamlining is.” From then on, it was known as the Beetle. Throughout the following years, Volkswagen Beetle continued to develop in both form and function, yet the style of the original car can still be seen in the in the new versions.

Greyhound Scenicruiser (1954)

by Raymond Loewy

The Greyhound Scenicruiser was introduced to Americans as a representation of the American dream. The highway bus was manufactured by General Motors for the Greyhound Corporation and designed by the godfather of industrial design, Raymond Loewy. Between 1954 and 1956, around 1,001 units were manufactured. The bus used to carry forty-three passengers and included air-conditioning, panoramic view windows, a restroom, and air suspension ride.

The split-level bus used to have ten seats in the lower level and thirty-three seats in the upper level. Due to delays and running behind schedule, the bus was rebuilt with 4-71 engines by Marmon-Harrington Corporation, which supported the bus with four-speed manual transmission. However, the bus was hard to maintain due to its complicated nature and additional systems, which resulted in a lack of diagnostic tools and technical support. As a result, the Scenicruiser was removed from the roads in the 1970s.

Ericofon (1956)

by Gösta Thames, Ralph Lysell, and Hugo Blomberg

The Ericofon was manufactured by the Ericsson Company in Sweden and can be considered a big step in the telephone design industry. The phone was designed as one piece from plastic materials. The dialing ring was located on the bottom of the phone, making it easy to use, especially when in bed and hard to reach a normal phone, which gave its consumer the taste of luxury. The Ericofon was introduced in 1940 by a design team that included Gösta Thames, Ralph Lysell, and Hugo Blomberg and was first produced in 1954. However, the series production did not start until 1956.

The Ericofon was introduced to European and Australian markets and later was able to enter the American market, although hard competition from the Bell Telephone company dominated the American market and refused to accept the foreign phone. The Ericofon was available in eighteen colors, and its sales were successful, as it exceeded 500 percent of the company’s, capacity. Later in 1967, Ericsson modified the design to be shorter and in a one-piece shell instead of two pieces. However, the newly designed model ushered in the end of the Ericofon era because of its poorly designed plastic parts and the hook-switch mechanism, which broke easily. Ericsson stopped the Ericofone’s production in 1972.

Braun Sextant Razor (1961-1962)

by Gerd Alfred Müller and Hans Gugelot

The Braun Sextant razor is one of the product design icons in the 20th century not only because its innovative shape, but also its influence on other razor models that followed—including designs in 1961 by Gerd Alfred Müller and Hans Gugelot and introduction to the market in 1962. The design of the Braun Sextant razor SM31 was lauded for its ergonomic quality, the measurements, the volume, and shape, which made it a design icon, especially with its black and silver model.

The Braun Sextant SM 31 recorded eight million units sold. In 1963, Richard Fischer designed the Commander SM 5, which introduced a radical evolution in the SM 31 design, as it included rechargeable batteries, which made it much easier to use.

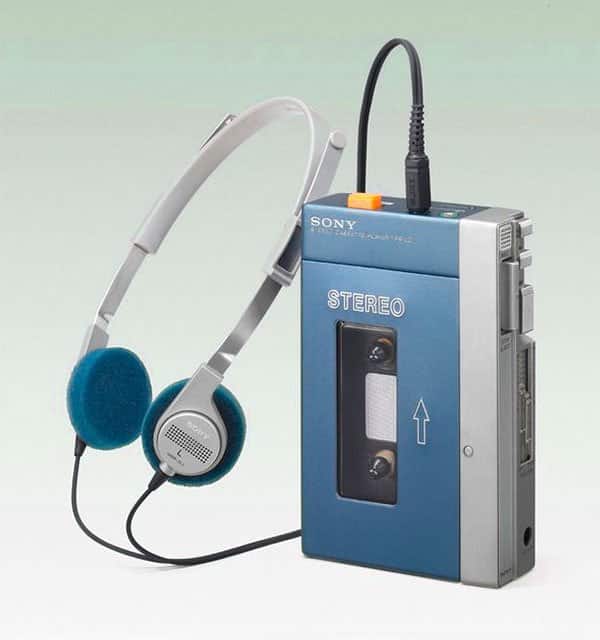

Sony Walkman (1979)

by Sony Design Center

What made the Sony Walkman special is that it allowed people to listen to music while walking or moving from one place to another. Sony’s Walkman became part of youth culture in the 80s and 90s. The Sony Walkman was first sold in 1979, and within ten years, 50 million people owned it. The idea of the product was inspired by Sony co-founder Maseru Ibuka, as he wanted to find a portable way to listen to opera music. Then, the product was assigned to designer Norio Ohga.

The Sony Walkman was the core of Sony’s most successful products including the CD, Mini-Disc, and MP3 players. A total of 400 million Walkman units were sold, and 200 million were cassette players. Sony retired the cassette Walkman in 2010, but the name prevailed in different generations and inspired the industry for revolutionary products including MP3 players and iPod devices.

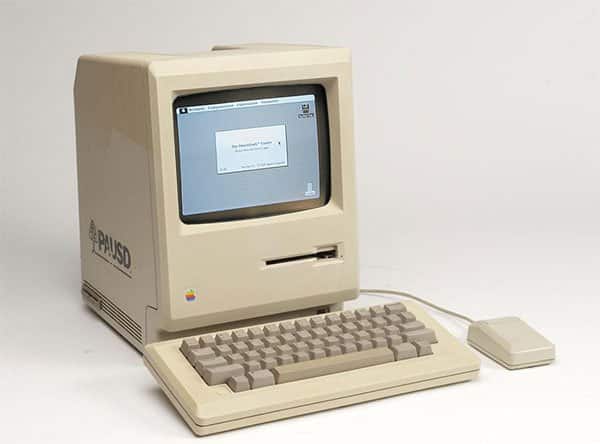

Apple Macintosh (1984)

by Hartmut Esslingen and Frog Design

What makes the Apple Macintosh special—and a departure from computers at the time—was the graphic user interface (GUI). Users were able to operate the computer by clicking on icons rather than writing commands. The first Macintosh computer as released in 1984 with 128K RAM and then upgraded to 512K RAM. Although there were concerns about the small and limited screen, its GUI operating system probably saved the Apple from death.

The Apple Macintosh 128K didn’t have any options to expand the storage, memory, or graphic cards, and it needed special tools to open the case. However, the Apple Macintosh allowed the middle class to use computer graphics, which had not been available without hardware that cost US $100,000. This revolutionary step to fulfill the people’s needs ensured success not only for the Macintosh computer but for subsequent Apple products.

The above examples indicate how design changed life during the 20th century and helped us draw a picture about how some product designs contributed to evolving the industry and how we think about design. If we intend to identify the shared characteristics that contributed to turning the above products into icons, we observe that the above products were introduced to either provide value, solve a problem, or make people’s life much easier. This conclusion can give is an idea about one of the most important roles of design as a problem-solving tool. Product success can be achieved when people’s needs are placed at the heart of the development process.

Enjoyed your article and hope to learn more and polish my critical thinking skills through my Design History unit at the University of Tasmania.