Leading Economy Through Design: Applying National Design Policies

In order to identify where design lies in the creative process, there should be a clear understanding of design and the difference between design, innovation, and creativity. As described by Sir George Cox in his “Cox Review of Creativity in Business: Building on the UK’s Strengths,” while creativity is the generator of new ideas and solutions, innovation is the process to apply that creative output. Design links both to reshape the creative idea into a final product.

In the world of competing economies, nations are always in search of strengths that can help its economy stand steady in front of emerging markets. Design and innovation can be important factors that can contribute to the success of not only companies but also domestic economies. My previous article about design and strategic thinking outlined results from Design Council research in 2001 that indicated design’s role in increasing percentages of capital turnover, profits, development of new products, and cost reductions.

Applying design as a nationwide strategy can increase this impact, especially with the support of governments that are able to facilitate design services for small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs). Design is not only used for new product development (NDP) but also to solve social problems through innovation and creativity.

Starting in the late 1990s and 2000s, nations began applying design strategies that over time have been proven successful, as in the cases of the United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea, and Finland. Additionally, an increasing number of countries, such as Brazil, have adopted design policies at various levels, as stated later in this article.

Why Apply a Design Policy?

There are a number of factors that influence countries to adopt design policies, such as rising competency, better life for citizens, and a switch to sustainable solutions. But let’s be clear that the most significant factor that can convince governments to invest in design is to improve their competitiveness and move up in rank among the world’s economies. For instance, India is one of the countries that applied design policies in order to gain global positioning and branding of Indian products under the label of “Designed in India” or “Made in India.”

In the “Cox Review of Creativity in Business,” the United Kingdom applied design policy in order to compete with the emerging economies in Asia and South America. While these countries have market advantages due to their low wages and larger workforce, Sir Cox’s review indicated that the United Kingdom can compete with these economies through design and innovation.

Barriers to Applying Design Policies

The observations above give us a clear vision of how creativity, design, and innovation can be a strength for the economies of countries in the face of threats from other emerging markets, but this raises another question about the barriers that stand in the way of creativity and innovation in businesses.

A 2005 survey by the Institute of Directors Business Opinion shows a number of barriers to innovation, both real and perceived. These barriers are listed below based on the number of respondents:

- Cost

- Lack of in-house design or creative skills

- Lack of customer demand

- Manufacturing or development issues

- Access to external design or creative skills

- Regulatory issues / government bureaucracy

- Design is not important

Cox reformed the latter results based on the scope of the review in the following three barriers:

- A limited understanding of where and how greater creativity could be used to a business’ advantage.

- A lack of confidence that the investment, in terms of time, money, and disruption, will provide a return.

- A lack of knowledge about how to go about it or where to turn for help.

While these three barriers focus on knowledge and an SME’s understanding of innovation and creativity, many enterprises may have this understanding but do not have the funds or understanding of their customers to achieve it, as reflected in the Institute of Directors Business Opinion survey noted above.

Levels of Applying Design Policies

Countries are applying national design policies at different levels and with different implementation methods based on the service provided and the involvement in the economy. One of these models is defined by Gisele Raulik-Murphy and supported by Mette Bom in his article, “National Design Policy Improves Competitiveness” (published by Design Research Webzine), which described the elements of design policy as:

- Design support programs that target companies.

- Design promotion programs that target the public sector.

- Design education programs that target design education and training.

- National design policy applied at the government level.

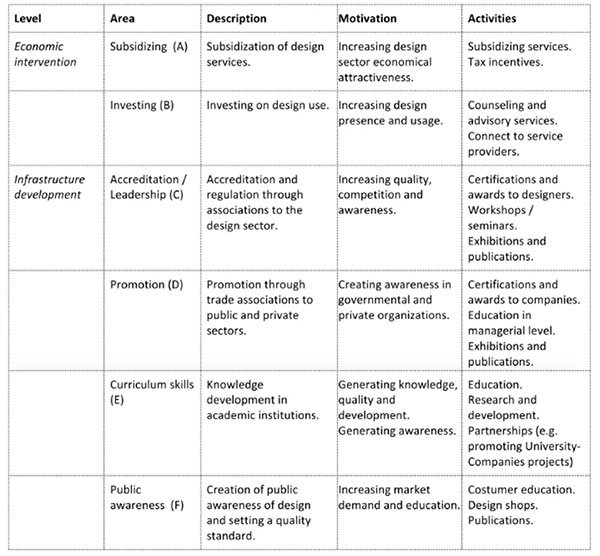

In 2011, “The Impact of National Design Policies on Countries Competitiveness” published for the Faculty of Industrial Design, TU Delft by a group of researchers provided a more detailed description of design policy based on the figure below:

Countries That Apply Design Policy

Based on the Raulik-Murphy model, many countries have applied design policies at different levels and with different elements. Countries like Canada, Australia, and Turkey are applying design policy in only the promotional domain, whereas countries such as India and Japan are applying a full design policy supported by their governments.

More countries are now adopting design policies, such as: Argentina, Australia, Botswana, Brazil, Canada, Catalonia (Spain), Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Flanders (Belgium), France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Iceland, India, Italy, Ireland, Israel, Kenya, Latvia, Mexico, Poland, Qatar, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, Turkey, United States, Venezuela and Wales (UK).

In the Design Policy and Promotion Map, you can review the array of countries applying a design policy through interactive experience and read a brief summary about each one’s experience.

Impact of Applying Design Policies

In order to evaluate a design policy, an action plan should be considered in order to implement the policy nationwide. In both the British and Indian experience, action plans were very similar in their focus on providing support and training. In the United Kingdom, the government implemented the Cox Review strategic plan through the “Designing Demand” program that aimed to help SMEs increase their creativity and innovation. The program was implemented in different areas of the country and served more than 6,000 companies through consultation and training.

In India, a research indicated the establish of service centers called “Innovation Hubs” were implemented to provide training for the automobile, jewelry, IT, and games industries. In addition to the government hubs, countries seek collaboration with universities and research centers in order to offer early training programs and cultivate better insights as to the impact of design policies.

The impact of applying the design policy in the United Kingdom appeared in The Annual Innovation Report 2012, which indicated a slight increase in the country’s gross expenditure on R&D (GERD) for the period of 2005 to 2009.

In another example, Finland’s application of a national design policy helped its economy jump to second in the World Bank’s World Competitiveness Index with the highest investment in R&D in Europe, at 3.5 percent of its GDP.

Design generates a significant impact in today’s world, not only at the level of individual companies but on a nationwide scope through design policies. The growing number of economies that depend on design and innovation as an important competitive factor indicates that design plays an essential role in the future of nations. As time goes on, more countries will be implementing design polices and expanding their design policies.

Note: the data discussed in the this article has been sourced from a variety of articles and resources that may not be up to date.