Applying Design and Innovation Framework in the Syrian Refugee Crisis

Many European organizations have started looking at design tools to solve societal challenges such as integration of new migrant intakes. The solutions range from creating products, services, and toolkits to education and training. Fortunately, we are beginning to see a great deal of adaptation of human-centered methods into political and societal problems, and the expansion of design tools is growing from the private and NGO sector wider to the realm of bigger organizations involving policymakers. From collective short-term initiatives and think-tank like workshops, there is a growing interest by the in-house team to look at the challenge as change management and seek uses for design thinking techniques.

Having recently adopted design thinking, UNHCR is looking into capturing innovation, which has derived from fieldwork, volunteers, and employee ideas systematically. UNHCR is created to promote and share creativity across the organization’s dedicated innovation unit. This allows us to amplify good practices that already exist, to connect good ideas to resources, and draw expertise from private and academic sectors.

The aim of the UNHCR Innovation is to work under four head team labs, test and nurture promising new ideas into full-scale sustainable solutions, and foster innovation amongst our staff and partners. UNHCR Innovation has also launched Refugee Challenge with What Design Can Do in partnership with IKEA Foundation. The online platform allows anyone to submit their idea, publicly vote, and comment on others, and the top ideas receive funding for further development.

Last year, Openideo also launched Refugee Education Challenge under Amplify Programme, funded by UKaid, to source bright ideas on how to remedy the disruption of refugee education or lack thereof. The project set out missions such as learning spaces, student wellbeing, teaching approaches, and the exchange of skills that the participants have submitted with their relevant ideas. Out of 376 ideas, five top-voted projects have been selected and funded.

Another project worth mentioning is Guts to Change, a new politician and designer-led initiative. Petitioned by Norwegian parliament and led by service designers with an idea to look at the migration to Europe and Norway, this program tries to see the challenge as an opportunity for collective action rather than a crisis. The project brings policymakers and designers on board to look at the allocation of resources in Norwegian society to benefit both the migrants and the citizens.

Just recently, in February 2016, the yearly European Social Innovation Competition was launched. This year’s theme, Integrated Futures, seeks innovative and creative approaches for products, technologies, services, and models that can support the integration of refugees and migrants. The competition focuses on social innovation projects within Europe and is only open to individuals, groups and organizations across the European Union and in countries participating in the European Horizon 2020 program.

The Syrian war and the refugee crisis have been ongoing since 2011. The escalating population of refugees arriving in European territories in the last eight months finally gained the attention of the Western media and helped many initiatives emerge. This social change brought about a lot of perspectives. The problem is not being exclusively left for politicians, governmental, or non-governmental organizations to solve, but also widespread use of creative tools and design-led partner solutions.

This report intends to explore how designers can take part in the refugee challenge and how they can use their skills to contribute to finding innovative solutions. First, I will investigate the recurring issues and the currently adopted solutions in order to identify where designers can make an impact.

How has the refugee crisis been dealt with so far?

The biggest challenge for most hosting countries is refugees’ right to work and the demand for public services. Refugees who come to host countries possess skills and experience in many different fields. Some were engineers, teachers, doctors, or designers in their home countries before the war started. They come here to find peace, do what they are good at, and contribute to and integrate into society. Statelessness not only comes with monetary adversities but also detains migrants from participating in social life. They remain alienated in their host society. As E.F. Schumacher has said, “If a man has no chance of obtaining work, he is in a desperate position, not simply because he lacks income but because he lacks this nourishing and enlivening factor of disciplined work which nothing can replace.” And in countries like Turkey and Lebanon—which hold the greatest numbers of refugees without the right to work—refugees are forced to work illegally at under-qualified and underpaid jobs.

Solutions encourage people to get to know refugees by highlighting their resilience and dispelling myths about them being passive receivers of aid or threats to local jobs. For this change to happen in each hosting country, we can also campaign for policies that encourage companies in the host countries to recognize refugees as employable individuals and create a quota system for refugee employee intake.

Creating jobs for refugees comes with its own problems, such as legalities and sanctions. Job priority is given to a country’s own citizens unless an immigrant is proven to be more qualified than all possible candidates for the job. Work permits are hard to obtain, and countries should issue more work permits.

However, countries such as Uganda and Jordan are leading a change and inspiring hope in refugee management. Uganda allows refugees from Burundi, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo to have the rights of citizens and access to public funds. These initiatives provided opportunities to many refugees by enabling them to set up their own innovative businesses and entrepreneurial endeavors.

Very recently, Jordan started to show signs of hope. Despite the fear of high domestic unemployment, a new strategy would allow Syrians to work in industrial zones and labor-intensive projects that are close to Zaatari camp. This new strategy is a step towards providing them with opportunities to flourish instead of dismissing them as dependents of humanitarian assistance. In hindsight, settlements on the outskirts of Amman may turn camps into slums in the future, leading to a bigger class gap in Jordan.

However, promising changes of policies on the migrant crisis open up an opportunity for design innovation, which can align with the proper cultural investment to lead to reforming ideas and groundbreaking projects. This transformative shift in refugee policies can be turned into an area of discovery for impactful design. During this transitional phase of camps becoming towns, refugees with steady wages and capital, leaders in cultural innovation, critical thinking skills, creativity, and knowledge economy is more necessary than ever.

Changes may be well grounded in the new creative environment by adopting the mentality of working with rather than working for refugees. For example, access to sets of thinking tools and frameworks could open opportunities for them to create their own jobs. As designers who are looking to create the biggest positive impact on this new environment, we ought to serve the needs for the longer term rather than short-lived, one-off design solutions.

One of the recent design innovations, making bags out of unused and thrown-out life vests, has caught quite a lot of media attention. This serves the needs of a certain demographic of refugees who are “on the go” and have not settled, staying in limbo. It is a nice project on its own, but it is far from a sustainable solution. It is essential to look beyond the emergency phase and think of ways design can contribute to providing opportunities like connectivity, electricity, education, right to work, and access to capital banking.

Out of all displaced Syrian refugees, only 10 percent are living in camps, 1 percent have the chance to legally settle in a developed country such as the U.S. and Canada, and 75 percent are living in urban destitution. And lacking access to jobs, education, and health services, in addition to poor living conditions, forces them to illegally pass to Europe by boats or on foot.

Focusing on helping solve the problems of those who settled could prevent bigger problems, namely, alienation from society, which can create an amplified impact. The majority of refugees’ ultimate goal is to settle in a country until the war ends. However, the current political situation doesn’t look like it is going to improve any time soon, and refugees are here to stay. They will become one with us and contribute to society.

What can a designer do?

Aside from working for or with organizations who employ service design tools to look at the challenge from different angles, I am quite interested in what an individual designer could do to get involved in this. Through this volunteering experience, particularly those who volunteer in the field in the Middle East, I have seen much suffering from burnout syndrome caused by the complexity, gravity, and magnitude of the environment. Best are those who live and breath the problem, but also have not burned out.

A project needs to be well understood by the volunteer himself even before the idea is submitted. He should be out in the field testing the idea. As a designer who is looking for her own ideas and ways of helping, I have found the techniques below useful.

Out of the many frameworks we could adopt to identify the challenges, the most powerful tool is perhaps ethnography. As designers, we are not qualified to become anthropologists. However, we have many reasons to rely on their techniques to inform our design or co-design solutions. While anthropology is concerned with defining the culture based on observable data, design is focused on creating solutions.

Volunteering experience is one way of really getting to know the aspirations of the refugees. My own experience included working at the camps, being a helping hand to different workloads, packing, handling, and setting up classes.

Through the experience of meeting and having conversations with refugees in camps in Suruc and urban settlers in Beirut, Amman, and Istanbul, I have come across very diverse refugee stories with varying pains, needs, and aspirations. These refugees, as different personas, are on a different path of survival on this journey than those who have settled, those who are still striving to reach their destinations, and those who are living in camps. Since the war began in 2011, many have fled the country at different times. Every individual is at a different stage in his or her journey. Some managed to find jobs and support their families, and some are still living with very limited means. To actually meet these refugees and hear their stories and aspirations from them is an unbeatable insight and advantage.

You might have seen a lot of people sitting in groups in a room with Post-it sticky notes and Sharpie pens, trying to brainstorm on some processes. This is how most change-maker workshops are handled these days, which is indoors and can be quite enthusiastic for all, but it is far from the reality. This is a good way to bring people with different backgrounds and expertise together. However, if you have not experienced it firsthand, it’s much easier to arrive at incorrect assumptions.

To understand the context and to evaluate the opportunity and movement gaps, I think it’s important to informally survey the real sufferers of the issue and then get indoors to flesh out all data gathered. One of the main risks is the poor practical application of research conducted in fields. And from my own brief career as a user experience designer—who likes to conduct her own user research, such as one-on-one interviews and user tests—I can also see the benefit getting involved in research. Design can be quite useful indeed.

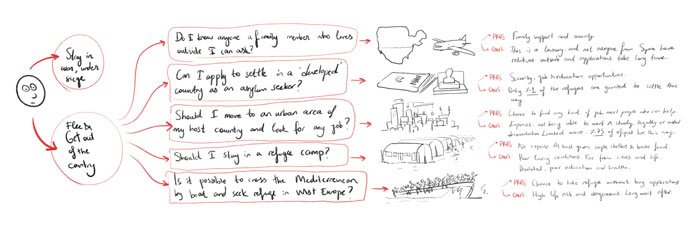

Then comes the mapping of findings from the fieldwork—the refugee journey and their decision-making criteria: Refugee Journey Mapping. This could also be done a step earlier, even before going out in the field, and then comparatively adjusted with evidence-based insights. This exercise is for us to get into the minds of the users whose problems we are trying to solve. What would you do in this situation? What decisions would you have on your plate? You might ask yourself, do I have money to start my own business in a different country? Do I have a family member in a European or neighboring country that I can live with for a while? Should I leave my family in the camp and find work in the city? Should I flee to Europe by boat, as it is easier than by foot? Mapping all the pros and cons, informed by fieldwork and the stories we are told, would help us to better understand the problem matter and the “personas.”

Which refugee problem we are trying to solve?

The more targeted we act, the more efficient results our solutions can produce. Amongst all refugee stories we have heard, whose problems will we be choosing to solve?

What are the user behaviors and limitations we have for our targeted refugee persona?

We may find out that most refugees have phones but not smart ones, and connectivity could be a problem. Therefore, creating an app for them probably won’t make sense unless we find another mechanism to support them with applicable devices, such as setting up a crowdfunding campaign to support refugees in camps and urban areas with connected devices, etc.

How can we prototype this idea?

Can we self-fund the initial prototype to see if it’s working? If we need funding, who can benefit from this project, and who can be other potential stakeholders who can contribute? We can look at who would be interested in partnering with us on this project, what they can give and return, and how they can benefit from this project. Do we need to fund this idea? Who would be the best people to pitch to, and why would they be interested?

Also, what skills do we need to prototype this idea? Do we need to start learning Arabic or programming? (Programming is probably the easier option here.) How could we work with people to release the first prototype?

How can we know that we created the impact we wanted?

Think of how you would measure the impact over time. For example, if you want to improve the literacy for the kids who can’t go to schools while in camps by increasing the literacy rate over time, how would you know you reached your target? Could you utilize short reading and writing tests at the end?

The hard thing about measuring social impact is that we have to deal with very long time frames—sometimes lifelong. Ideally, you want to keep in touch with the students you worked with and measure how the course you designed increased their quality of life. But with refugee communities, this is even harder, as you probably won’t be able to get in touch with children you worked with later. However, there are ways we can design to keep in touch with the kids, such as recording names and setting up mailing addresses for regular yearly information exchange. It’s always good to keep these in mind.

The importance of thinking about the impact we want to create firsthand is that will ultimately drive our project. It is not the language course we intend to set up, but the impact we want to produce at the end of the day. So the earlier we clearly outline our hypothesis (or several hypotheses), the easier it will be for us to stick to reality and be result-oriented rather than become infatuated to our solutions, which may not work.

To apply hypothesis framework here, we can consult Lean UX methodology by Jeff Gothelf:

We want to increase literacy [results] at this particular refugee camp [where] by organizing language classes [what] because we think it will increase the life quality of the refugee children in their lives later on [why].

Production and moving forward

You might be familiar with the design thinking process: ideate, prototype, and iterate. Once the first prototype is out, it is incredibly important to record all the findings in terms of what worked and what did not work. Receiving regular feedback from the refugees on our prototype as well as from the internal team is a great way to make things better. The feedback mechanism could be in any form and can be completed informally over coffee, as a conversation or simply a collection of observations as a diary or daily check-ins about what went right, what went wrong, and ideas on what could be improved.

Some questions we might decide to ask regularly in these meetings include:

- Does the solution we provided match the affordances of our users? For example, following the language course idea, is the curriculum easy enough to understand? Is the pace of learning easy or hard to understand? Should we slow down or speed up?

- Is it sustainable? Do we have all the means to support this project, monetarily and mentally? How are participants and volunteers feeling? Is anyone feeling burnt out? Does anyone need emotional support? How can we make it into a more sustainable system?

- What are the barriers and how can we solve them? Let’s say we are running our language classes, and we are starting to see dropouts by female students. We find out that their parents don’t want them to participate in the classes so that they can look after their siblings. Could we re-iterate our program to fit the needs of these changing situations?

What are the volunteer-run projects, and where do they sit on the Impactful design matrix?

We as designers, particularly, craft our projects and outcomes within the scope and potentials of our professional skill sets. As such, product designers tend to think in a more three-dimensional fashion, whereas graphic designers have stronger communication skills. Leveraging our qualities with qualitative data we gain on the field can lead to outside-the-box solutions.

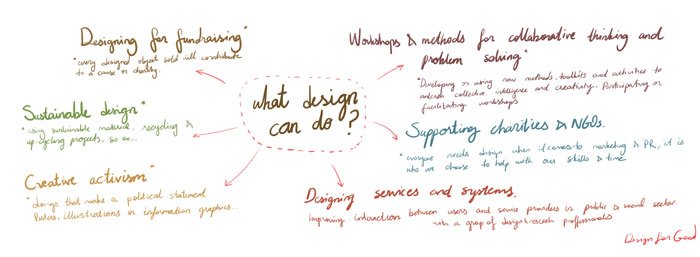

I have created a template, which I decided to call an Impactful Design Matrix for Design for Good. I did this to map the change-making projects I came across recently, with one or two sample projects for each category. I am sure I am missing an awful lot of projects that should be mentioned here, but this is just to give you an idea. If you have or know about a great project, please let me know!

Product Design

Here, “products” is defined in the most traditional sense: impactful industrial design solutions made of sustainable material or made with recycling or upcycling processes. Many of the most successful designed products are the ones that have a system build around them and those that operate in this system in coordination with others. Even if it did, I guess it would be an unsustainable one.

- You may have recently come across the news that volunteers at Lesbos are “upcycling” life vests into handbags and backpacks. Led by several different people, this upcycling project aims at making something useful out of life vests dumped in hills on the shores of the Greek Mediterranean. Read more here.

- Cucula studio in Germany, founded by a friend, Sebastian Däschle, is a furniture design company who is giving refugees in Germany a studio to create and sell their own design. I find this project particularly great because it is creating a bigger value than products, actually giving refugees work and space to practice their creativity.

- Studio Refugee in Belgium, Genk is matching graphic designers with refugees to jointly make products that tell stories. The studio provides free sewing courses for refugees, and purchasing a product from the studio means contributing to the maintenance of the process.

Service Design

Service design is not looking at the end product on its own but taking a holistic approach. It requires the use of different research methodologies in order to better understand the processes and therefore produce useful, desirable, and effective results. The outcomes can be tangible or intangible; it can or involve artifacts or can be on an environmental, behavioral, or communicative level. The most successful designed systems would be those that look at sustainable solutions, engage in problems thoroughly, and improve interactions between all of their users. In this context, the use of service design tools can help improve communications between governments, citizens, and volunteers with refugees.

- One of the most successful and leading example of sustainable system design I have seen on this (and my favorite until now) was Refugees Welcome network, which aims to find housing for migrants in urban areas. Started in Berlin, it is now spreading to other countries and cities. The project not only provides shelter to the person but gives them full cultural interaction and integration. The system is pretty simple but very impactful, just like how Airbnb matches the house owners who have available rooms with asylum-seekers and runs a crowdfunding campaign aside to cover the expenses of the room. It’s awesome because, as a project, it fosters innovative social models and behaviors. This makes it just brilliant.

Creative Activism

Medium is the message. Creative activism is about making your political statement in an artistic and peaceful way. We know many musicians, artists, and dancers who made a difference in this world by expressing their ideas in their craft by stating the unspoken—the forbidden. Applied in the context of design, particularly in visual communication and graphic design, this can translate into visual political statements posters, illustrations, and information graphics.

- Seeing Data is a visualizing project amongst others that puts migration in perspective. Visualizing data is a great way to inform people about the scale of the crisis as well as making the underlying idea easier to grasp.

- What Ai Weiwei is trying to do with his recent work in Lesbos and Turkey would also sit here. Whether it was a successful attempt or not, I guess he was trying to explore the ways in which art could be involved in migrant politics.

Collaborative Workshops

This category includes workshops and use of methods from different practices such as Participatory Action Research as well as Design Thinking for collaborative thinking and problem solving. I wanted to make a distinction between service design and collaborative workshops as separate categories, though service design can and should involve the processes of the methods above. I should also add that the organizer or facilitator’s role here is to assist the community to come up with their own solutions rather than a handover approach.

- This is where I stand with Design for Good. The project began as I went to volunteer at one of the refugee camps at the Turkish-Syrian border town Suruc. During this time, I started facilitating art classes and have observed hundreds of children’s drawings. I came to witness the therapeutic and self-expressive impact of art on children affected by the war in Syria. When I went back to the camp two months later, I saw that the 10,000 refugees living there at the time shrank to 500 people, as they had begun to go back to cities and across the Mediterranean. The next stage of the project is working with asylum-seekers and urban communities, particularly with young teenagers between the ages of 16 and 20. Workshops will begin trials this month to aim to make design thinking accessible to all to foster entrepreneurial and social skills.

Conclusion

I talked about recently launched competitions that are looking to explore the reserve of creativity and collective intelligence within society. Acknowledging each person in the community can actually contribute to the challenge with their own different and unique critical mindsets. This strategy seems like it will bring change to how we will tackle political problems from now on. Instead of seeing the problem as a large picture and trying to solve it as a large organization, it seems more effective to endorse self-initiated projects and seek resolution in smaller steps.

Use of research tools I previously mentioned can help us reveal the actual problems we are trying to solve. Getting out in the field and experiencing the problem firsthand is invaluable. By spending time with the refugee communities—backed up with service design methodologies such as understanding and regularly checking our hypotheses—journey mapping can make our approach more grounded.

Migration is one of the biggest challenges currently facing European society. If the new approach of incubating solutions through public participation succeeds, it means we have achieved beneficial progress. This could lead us to attain tools and practices to solve even more complicated problems such as terrorism, radicalism, and racism in society.