SCAMPER Technique Examples and Applications

The SCAMPER technique is one of the brainstorming tools that allows us to explore solutions to problems by altering the current product through seven different approaches: Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put in Another Use, Eliminate, and Rearrange. My previous article, A Guide to the SCAMPER Technique for Creative Thinking, explored these seven approaches and the questions we must ask ourselves to solve a design problem. In this article, we will examine examples of the SCAMPER technique and how it is applied in the real world by different companies. To build a holistic approach that can contribute to better application of the SCAMPER technique, we need to adopt a system thinking approach in addressing problems. This means that we don’t think about the solution from the perspective of the product alone; we need to dig deeper and see the whole system, including but not limited to the human factor involved in it.

Before moving forward, the SCAMPER technique is a brainstorming tool, but it doesn’t come at the early stage of the design thinking process (Discover), as many assume. It is based on previously collected data and defined problems. This solution brainstorming technique can be used in the third stage of Double Diamond design thinking (Develop). You can use IBM design thinking during the third stage (Make), where we explore the solution for the defined problem in the previous stage (Reflect). However, in IDEO design thinking, the SCAMPER technique comes in the divergent stage of creativity before the final converging part of the ideation stage.

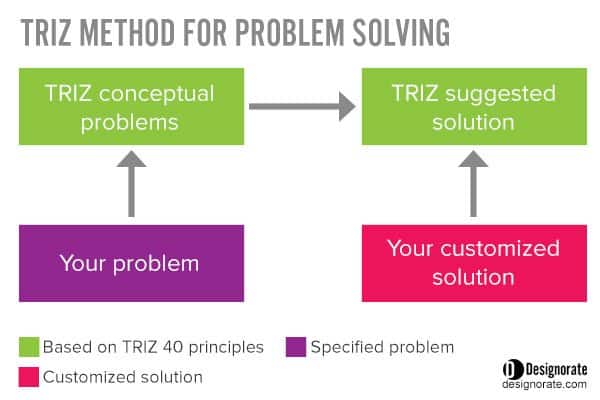

The SCAMPER Technique vs TRIZ method

The SCAMPER Technique is an exploration tool with a divergent nature. It allows you to explore the different alternations of the system and see which one is applicable to achieve the intended value. On the other hand, the TRIZ method for problem-solving is more systemic and follows specific conditions to map the problems and find suggested solutions based on predefined solutions. This is due to the concept behind the tool, as it says that we can solve any problem if we can identify the problem pattern and map it to similar problems’ solutions, which leads to saying that there are 40 routes to solve any situation in the world.

The SCAMPER and TRIZ methods take different approaches to solve problems. The former is more seen as a driver of innovation and creative ideas, while the latter is more like applying template solutions that fit more for tame problems, which are repeated problems that have been solved before, unlike the wicked problems in the design thinking process. Now, let’s move to each of the methods in the SCAMPER technique and see how it can be applied through real-life examples:

Substitute

This approach means substituting the problematic part with another to solve the problem or achieve an advantage. You can ask yourself what to substitute in the system to improve it. For example, how can you substitute one part of the product? Or can changing the brand logo improve the product image?

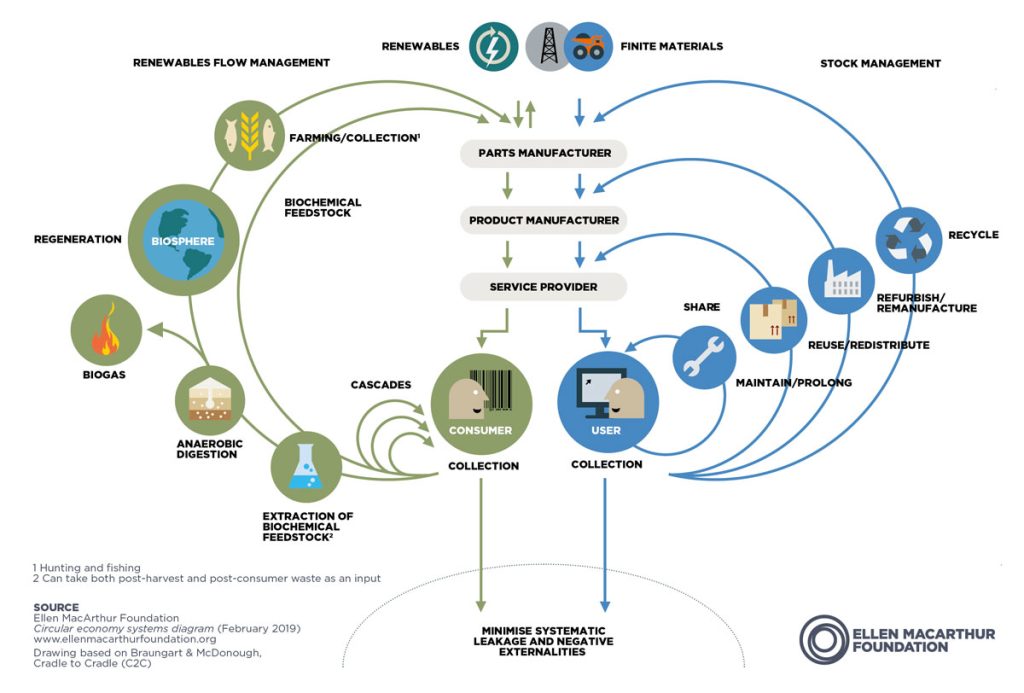

One of the examples of using the Substitute approach is IKEA. IKEA’s sustainability strategy (check Part 1 and Part 2) aims to reduce the usage of earth resources, especially the slow or non-renewable ones. However, they are the most famous furniture maker in the world. So, can they achieve the balance in this complex equation? IKEA’s sustainability strategy is based on the circular economy approach, reflected in their materials. Using wood from trees reduces the green forest, especially where IKEA manages the different forests, and these trees take a long time to grow again. Therefore, IKEA replaced the wood from trees that grow slowly with different materials, including fast-growing trees, recycled materials, metal, and mixed materials. This substitution contributed to reducing the wood usage as raw materials, using recycled materials, and reducing landfill waste.

Combine

Think of the different elements in the system that can be combined to solve a problem or achieve a value. This combination doesn’t necessarily have to be for similar elements; you can ask yourself what materials, Human Resources, products, or features to combine to achieve the intended outcome.

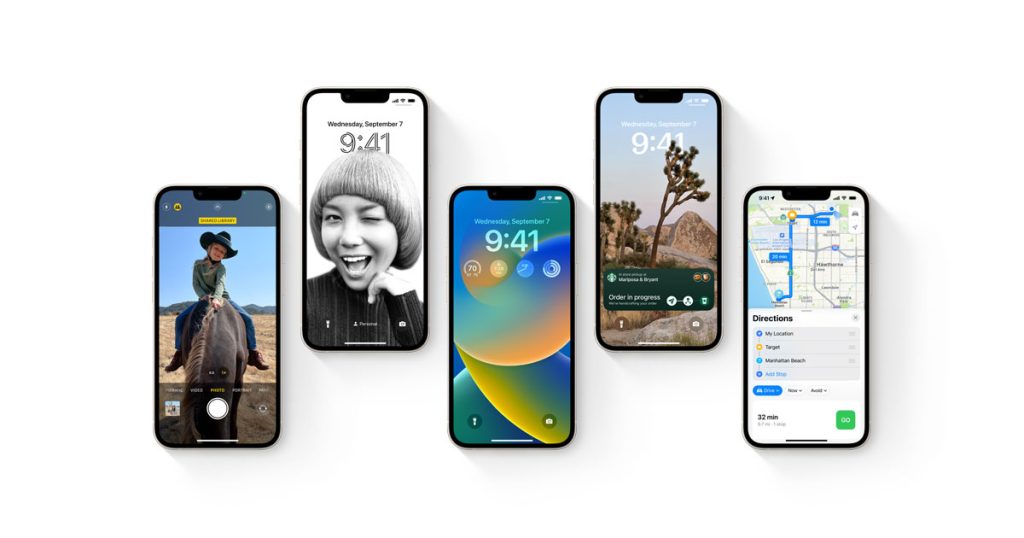

A perfect example of the combined technique is the mobile phones in our hands. At the beginning of the invention of mobile phones, it was a combination of two old technologies: radio and phones. Combining them created the concept of a phone that you can use anywhere without a wire. Then, the mobile phone evolved again using the same technique by combining all the different features people need on the go, such as cameras, which now extend to multiple cameras.

Let’s see another example from the chain supply industry. Companies that ship their products internationally keep their warehouses in the logistic area near the shipment routes. Combining the two activities helps companies reduce transportation costs, time, and carbon emissions. Also, it creates a centralised point where partners and different stores can collect the goods directly from the warehouses.

Adapt

The Adapt approach looks to the components of the problem and explores how to bring ideas from the sample product or other products or systems to utilise to solve the problem. Not only ideas, but you can also adapt components from other products or systems. Make sure to distinguish this from the Modify approach below. Adapt is about having an idea or element not part of the system and adapting it to use with the system to make the change.

A good example is Henry Ford’s idea of the moving assembly line in the automotive industry. The problem that faced For’s aims to streamline the mass production of cars, which can contribute to dividing and reducing the car product costs. Before For, the moving assembly line was used in other industries such as slaughterhouses. A moving belt carries the product across the product line, and each worker specialises in one task to complete, and the product moves from one point to another (What is the 8D Problem Solving? And How to use the 8D Report?).

Ford adopted the moving assembly line in the automotive industry In 1913. So, instead of the workers going to the car, the car moves to the worker, saving time and cost. The result was the mass product in the car industry and the spread of using affordable vehicles. While this created future problems with carbon emissions, as I discussed earlier about design thinking, yesterday’s solutions are today’s problems as we move into the arena of problem/solution space.

Modify (Also Magnify and Minify)

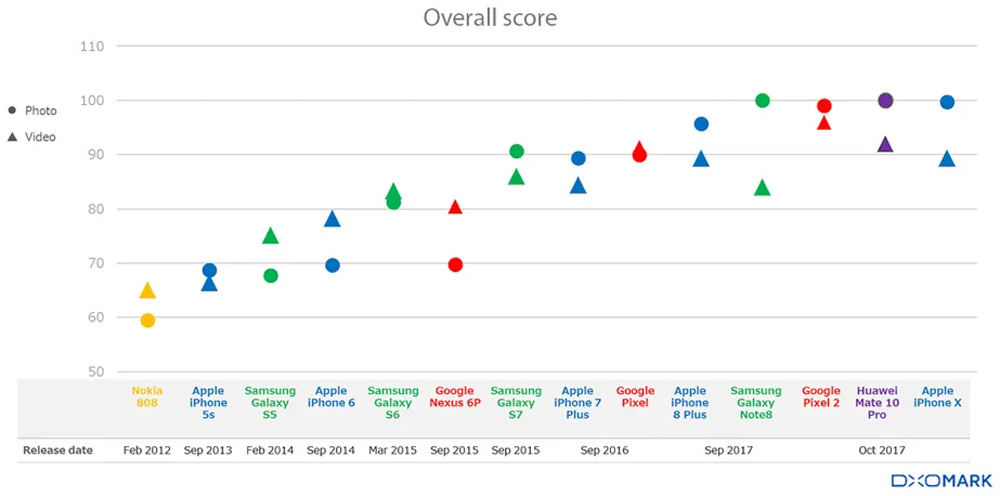

The term modifies in the SCAMPER technique here has a specific meaning; it refers to looking into the part of the system and seeing how magnifying or minifying its role can help improve the product. This modification can include its visual, function, contribution, or others based on the element’s role in the system. Another example from the mobile manufacturing industry is mobile cameras. In the combined approach, we explored how combining the camera with the mobile phone added extra value for consumers. This value extended the function of mobile phones as a photography tool to take selfies, record notes, take family photos, and video footage. The following approach was applied to mobile cameras through the Modify approach. Magnifying the role of the camera either by increasing its capabilities or its number to improve the quality of mobile photos and provide extended features for users, such as using a wide camera or taking high-quality images.

Another example from the UX design for mobile applications is the social media websites like Facebook. Visit any of the pages on your mobile, and you will notice that some buttons are more significant than others. The magnification of the buttonhole in the screen, such as its size, colour, or screen position. This increased focus drives users’ attention to the button and gives them more chances to click it.

Put to another use

In this approach, we take one element and change its function in the system to another for better performance. This element can be a product part, service, or human. This is about using one product and directing it to another market segment, so the concept is vast based on the situation you have in hand. The charging sockets in iPhones are put to another use as audio output, reducing the structure’s complexity.

In the circular economy, we use the SCAMPER technique in several ways, including the “put to another use” approach. For example, in the circular economy’s remanufacturing principle, reused or refurbished products are re-engineered, and their raw materials and parts are used to create new products. This concept applies to reducing the waste produced by different products and machines and, at the same time, reducing the consumption of earth’s resources (What is Circular Design? And How to Apply It.).

Eliminate

The sixth approach is to eliminate parts of the system to improve it. Will the system work better if we eliminate this specific part? How will removing it impact the rest of the system? Sometimes, the part of the product or the feature complicates the system because the product was simply a set of features added to each other over time.

One of the examples is eliminating the removal of DVD players from laptops. The problem in reducing laptops’ thickness is that the DVD needs to be more significant to solve this problem. Apple started this revolutionary step by removing DVD players from their computers and shifting user behaviour toward cloud storage and sharing. There were many questions and debates around this step in the beginning, but later, it was proven successful, making the rest of the companies follow Apple’s steps (Design Thinking Case Study: Innovation at Apple).

Reverse

Sometimes, it is clever to ask ourselves, what if the problem is in the order of the process steps, not the final product? Reversing the process or the production progress can lead us to the solution. In the Reversed Brainstorming technique, we do the same. Instead of trying to solve the problem, we try to complicate it, and through this ideation process, we tend to find out the real root cause of the problem and solve it.

Plastic bags were once a revolutionary solution for many shoppers to avoid paper packs that can be easily torn up. Also, it was a cheap alternative. However, plastic usage has shown how bad it is for the whole ecosystem, especially when it goes to landfills. Solving the problem was simple: reverse the progress and return to the paper bags. Making the bags more durable using new technologies is an excellent way to overcome the paper bags problem; so, as we drove consumers to use paper bags like in the old days, companies tended to find root-cause solutions for the packaging problem.

How to Use the SCAMPER Technique

The SCAMPER technique is an explorative tool. It doesn’t provide a direct solution similar to the TRIZ method we highlighted earlier. Therefore, it works well in a co-create environment. The team members explore how each SCAMPER solution can be used in the target problem and which needs to be more relevant.

The SCAMPER works well with the Double Diamond Design Thinking or any other design thinking processes because we can use it in the development stage to explore different solution prototypes and test the potential solutions to identify the most effective solution to solve the problem while considering all the system elements. In my previous article, you will find several examples of the SCAMPER questions you can share with the team to brainstorm and explore different solutions.

The SCAMPER technique is one of the most effective tools to identify the possible problem solutions and explore how to improve products, services, and systems as we saw in the above examples of each tool approach. So, it is crucial to consider this nature while using the SCAMPER tool and techniques and, most importantly, the team expertise involved in solving the problem.

Further Readings:

Eberle, R. F. (1972). Developing imagination through scamper. Journal of Creative Behavior.

Serrat, O., & Serrat, O. (2017). The SCAMPER technique. Knowledge solutions: tools, methods, and approaches to drive organizational performance, 311-314.